An API for The National Hockey League (NHL)

Introduction

The National Hockey League (NHL) is a professional ice hockey league in North America. It comprises a total of 32 teams, of which 7 in Canada EPL, including the Montreal Canadien. Each year, the Stanley Cup playoffs selects the best team, which is awarded the Stanley Cup for the season. For example, The Montreal Canadien won the Stanley Cup 24 for 24 seasons, the last time in 1992-1993.

The NHL makes publically available an API that features statistics including meta-data on each season, season standings, player statistics by season, and play-by-play data. This last format of data is the most thorough and it features important information for all events during each game, such as the players involved, location coordinates on the ice, and the type of event. The NHL API is a valuable source of fine-grained sports data that can be used in a number of tasks such as finding the features that predict goals, or those that predict players salaries.

Motivation

The purpose of this project is to provide a Python API for accessing NHL data, specifically, all the play-by-play informations. The reader will learn here how to download the NHL data for a given year, how to first visualize it, and then how to format it into a tidy data frame. This tidy data format will then be used for producing simple, as well as more advanced, interactive visualizations. At term, this data could also be used for a number of purpuses including machine learning, or other tasks at the reader’s will.

Installation

Setup Environment

- Git clone the repository

- Make sure Python is installed on the system

- Create a virtual environment / conda environment

Install Dependencies

- Activate the environment and run

pip install -r requirement.txtthis will download all the dependencies related to this project.

Usage

Download Data

- The data for the NHL games are exposed out in the form of various APIs, the details of the APIs can be found over here

- Run the python script which resides at

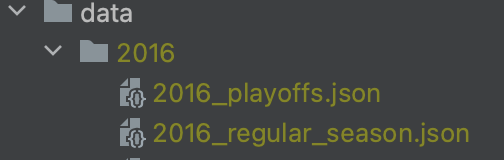

modules/dataextraction/data_extraction.py, this script will fetch the data of the seasons starting from 2016 to 2020. - This will create a folder in your directory for the season which you want to download and two json files will be

appeared along with some other files which will be used later part of the project.

YYYY_regular_season.jsonYYYY_playoffs.json

Run Interactive Debugging Tool

- Run the

jupyter notebooklocally inside the project folder - Navigate to the

notebookfolder - Run

3_interactive_debugging_tool.ipynbfile

Create Tidy Data for Visualisation

- Run the python script which resides at

modules/dataretrival/data_retrival.py, this script will creates the tidy data and save the data into a pickle file for all the seasons starting from 2016 to 2020.

Run Simple Visualisation

- Run the

jupyter notebooklocally inside the project folder (Incase if jupyter notebook isn’t running) - Navigate to the

notebookfolder - Run

4_simple_visualizations.ipynbfile

Run Advance Visualisation

- Run the

jupyter notebooklocally inside the project folder (Incase if jupyter notebook isn’t running) - Navigate to the

notebookfolder - Run

7_interactive_figure.ipynbfile

Project Structure

As seen in the above image, the project is divided into various parts,

data- It contains all the NHL tournament data season wise, in each season we have two json files of regular season games and playoffs.figures- It contains all the data insights which we captured in this project.modules- For every action which we are performing in this project, are captured as modules, like data extractions, data retrieval (data parsing)notebooks- For all kinds of visualisations, insights of the data can be accessed through the notebooks.constants.py- As the name suggests, all the common functions and variables reside in this file.

Data APIs

This project uses two APIs which were provided by the NHL :

GET_ALL_MATCHES_FOR_A_GIVEN_SEASON = "https://statsapi.web.nhl.com/api/v1/schedule?season=XXXX"- This API fetch all the matches metadata for a given input season, using this API we are getting the map of

Matches ID and the type of Match it is like

regular season or playoffs

- This API fetch all the matches metadata for a given input season, using this API we are getting the map of

Matches ID and the type of Match it is like

GET_ALL_DATA_FOR_A_GIVEN_MATCH = "https://statsapi.web.nhl.com/api/v1/game/XXXXXXXXXX/feed/live/"- This API fetches all the data in a granular form for a given match id, where we gather the insights subsequently in the following tasks.

- In order to download a particular data for a season, update the file

modules\dataextraction\data_extraction.pywith theyearvariable (one can put multiple seasons to download as well) - Once the update is done, run

data_extraction.pyit will download the data and place it under a folder with the season year with two json files, with regular season games and playoffs respectively.

Data Insights

Data Extractions

The data available by the NHL API needs to be parsed and formatted in order to make more advanced data usages possible. In this regard, we select the relevant data out from the nested dictionnaries from the json file, and and we format a single tabular structure, i.e. a dataframe. Below is a glimpse of the tidy dataframe which will be used in further analyses.

Tidy Data

How to get the number of players in each team

The first step would be to format a new tidy dataframe which would includes all types of events (not only the shots and goals, such as in the dataframe featured above), with events as rows and including datetime, eventType, periodType, penaltySeverity, penaltyMinutes, and team, as columns. The events would to be sorted in order of their occurrence in time during the game (datetime).

We would then create an empty (np.nan) column for the number of players on ice, and program a loop to iterate over all event, while concatenating a list of player counts for each time, n_1 and n_2. At the beginning of the loop, and at the beginning of each period (each time the period of the event is not the same as the previous event), we re-initiate the parameters: n_1 = 6 (number of players in first team, including the goalie), n_2 = 6 (number of players in second team, including the goalie).

Eight parameters would be set: penalty_player_A_team_1=None, end_time_of_penalty_for_player_A_team_1 = Datetime penalty_player_B_team_1 = None, and end_time_of_penalty_for_player_B_team_1=Datetime (as there can be a maximum of 2 players in penalty at the same time);and the four equivalent parameters for team 2.

Then, as the loop iterater over all events, each time the eventTypeId == “PENALTY”, if “penaltySeverity”: “Minor” or “DoubleMinor”, the number of player in the team involved in the penalty (Team of the player that is penalized) would be substracted 1, the penalty_player would be set to the name the penalized player, and end_time_of_penalty parameter would be set to DateTime + penaltyMinutes. For subsequent events, as long as the penalty_player is not None, the datetime of the event would be compared to end_time_of_penalty, untill datetime > end_time_of_penalty and then the number of player for that team would be added +1, as the player is back on ice.

Note that for other types of penalty (e.g. misconduct), the number of player on the ice would not be updated as an immediate player replacement is allowed.

Engineering additionnal features

We would be interested in studying the impact of tackling and hitting on the chance of goals, both (1) at team-level (2 variables), (2) player-level (4 variables), and (3) total through the game (4 variables). Indeed, tackling and hitting has become an important part of hockey, often discussed by commentators, and highly represented in the data under “eventTypeId”: “HIT”.

(1) We would first extract, for each shot event, variables at team-level that corresponds to the time (in minutes) between the shot and the last time a player of the team on which the shot was taken was hit. This would be done by iterating through all events in chronological order, initiating the time at as NaN at the beginning of each period, and updating the time at each time a hit happens, for each team. This would result in variables: time_since_last_hit_team_1 and time_since_last_hit_team_2.

(2) Additionally, during the same iteration process, we would update four boolean variables with player-level information to note whether the hitter and the hittee from the last hit event were among the player involved in the shot (shooter, goalie or assist). This would result in variables: hitter_involved_team_1, hittee_involved_team_1, hitter_involved_team_2, hittee_involved_team_2.

(3) Finally, to study the relationship between goals and the total number of hits in a game, we would extract 4 variables, during the same iteration process as above. These variables would be initiated at 0 at the beginning of the game, and updated at each hit event for each team and type of player involved (hitter or hittee). This would result in variables: n_hitter_team_1, n_hittee_team_1, n_hitter_team_2, n_hittee_team_2.

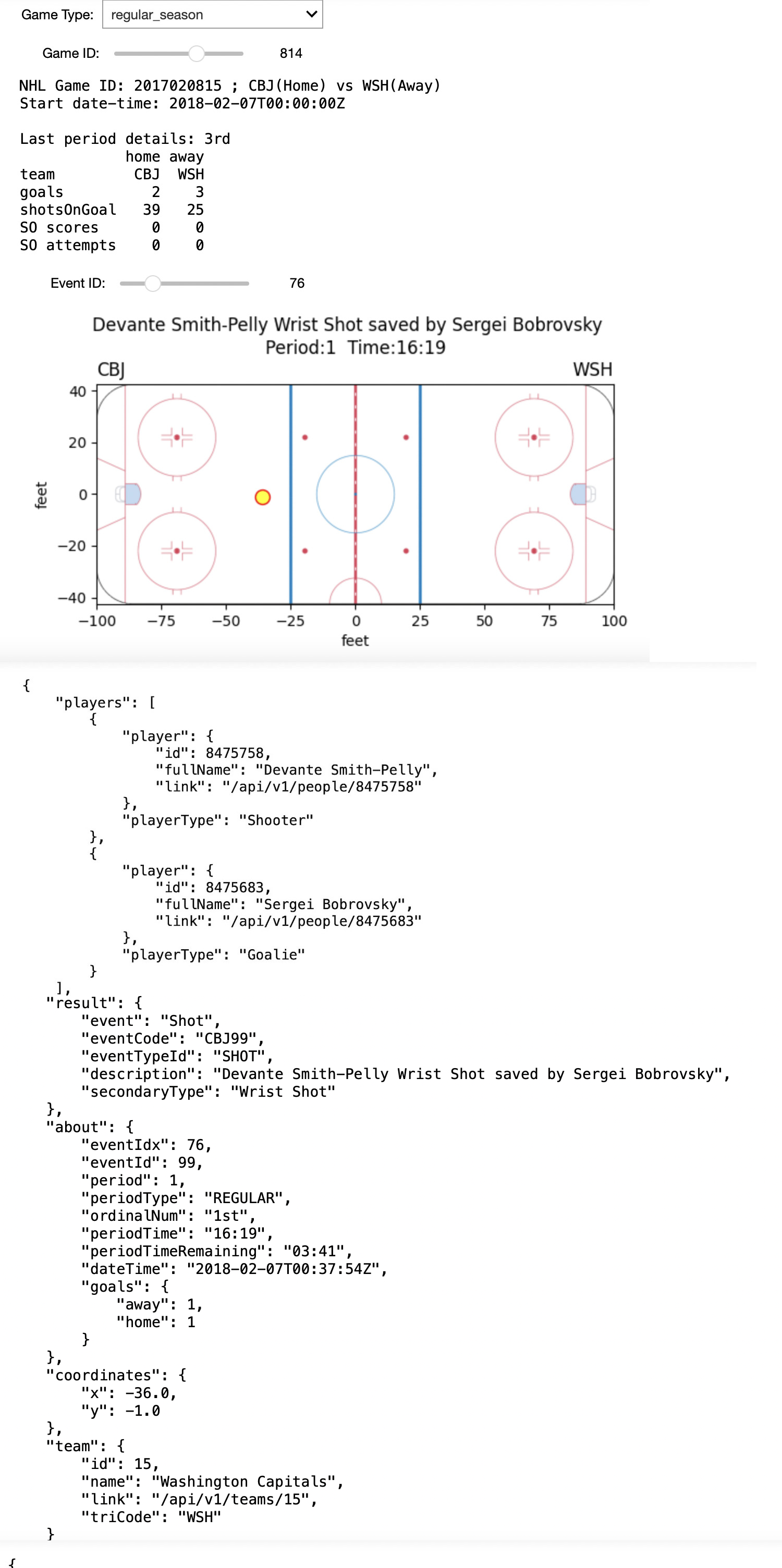

Interactive Debugging Tool

Event locations for the season 2020

Insights

Simple Visualisations

Goals and missed shots, by shot type for season 2016-2017

Insights

The most dangerous types of shots for this 2016-2017 season are “deflected” (19.8% of success) followed by “tip-in” shots (17.9% of success). By “most dangerous”, we mean that these shots are the ones that end up the most frequently by a successful goal, as opposed to being missed. However, these are among the less frequent ones: there were only 806 “deflected” and 3,267 “tip-in” shots this season. On the contrary, the most common type of shots was by far the “wrist shot”, with a total of 38,056 shots of that type for this season.We chose to illustrate this question with a barplot while overlaying the count of goals in blue overtop the total count of shots in orange (thus, total of both goals and other, missed shots), by type of shot. Even though there is a large difference between the most common and less common types of shots, we chose to plot the absolute numbers and to keep the scale linear, because these are the most intuitive for the reader to understand the scale (the great number of goals involved in a same season) and not to be confused with too many percentages on the same figure. We chose to add annotations on top of bars for the percentage of goals over all shots, because these proportions could not be visually abstracted simply from the figure, and this was an intuitive way to illustrate them.

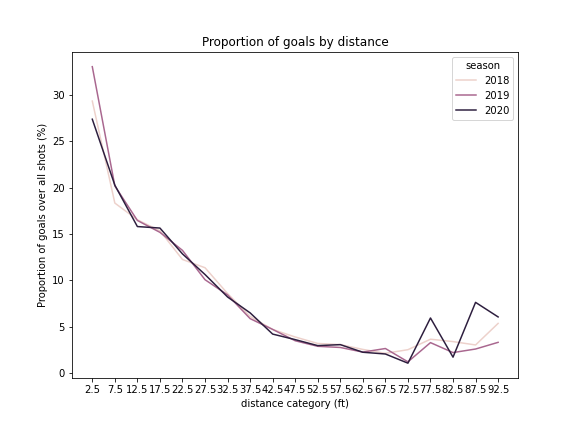

Proportion of goal by distance for seasons 2018, 2019, 2020

Insights

The proportion of goals over all shots increases overall exponentially as the distance diminishes, with a maximum proportion of goals >25% when goals are shot at less than 5 feet from the goal. We also note a small, local maximum at 75 to 80 feet. This distribution did not change significantly for seasons 2018-19 to 2020-21. This local maximum could suggest that there is another variable (e.g. shot type or other) that could underlie this distribution.

Proportion of goal by distance and shot type

Insights

We chose this figure after having considered and visualized different types of figures. First, we visualized violin plots of the distribution of goals and missed shots; however, these did not intuitively represent the chance (proportion) of goals over all shots per se, and the result was dependent on some assumption on the kernel size. We also experimented computing a logistic regression to predict goals from the distance category, which worked fine.Finally, we chose to come back to the most simple and intuitive method, which is to bin the distance into categories, and plot the proportion of goals for each bin. We chose to divide the distance into equal bins (as opposed to percentiles or other kind of distribution), in order to be able to draw direct conclusion about the relationship of goals to the absolute value of distance by visualizing the figure. Overall, the most dangerous \ type of shot is the “tip-in” shot taken at a distance of less than 5 feet, followed closely by “back-hand” shots: more than 40% of these shots result in a goal. The relationship found in the previous questions, i.e. that the probability of a goal augments exponentially as the distance decreases, holds true overall for most types of shots. However, the “deflected” and “tip-in” shots have a second maximum between around 30 and 60 feet.

Importantly, the “back-hand” shot has a second maximum at about 80 feet, and the slap-shot has a second maximum at more than 90 feet. This could explain the small local maximum at that distance that we observed in the global distribution of all shots at the previous figure.

Finally, the curves are somewhat irregular, and adding more data (e.g. averaging through a few years) could add more smoothness in the results. Note that to have more smoothed curves and remove outliers which made interpretations difficult, we did not plot the points for which we had less than 10 total observations for that type of shot and at that distance in that season.

Advanced Visualisations

Comparison of Colorado Avalanche avg shots between season 2016-2017 and 2020-2021

Here, we compute the average shot rate per hour for each team and for each location on the ice, rounded to a square foot, as compared to the league average shot rate per hour for that same location in years 2016 to 2020, and normalized by the latter. Formally, we compute:

((team average shot rate per hour for location k) - (league average shot rate per hour for location k))/ (team average shot rate per hour for location k).

We then display the result for each square foot on the ice, as a heatmap overlayed on a figure of the hockey rink, for the offensive zone. The heatmap was smoothed using a gaussian filter with sigma=5. We plot independent figures the years 2016-17, 2018-2019, 2019-20 and 2020-21, with option to choose the team to display.

Season 2016-2017

Season 2018-2019

Season 2019-2020

Season 2020-2021

Discuss the interpretation of the figures

These figures display the excess shot rate per hour by ice location for the team and year, normalized by the league average for all teams and years (2016 to 2020). The excess shot rate is displayed as a proportion of the league average; it is important to look as the scale from the side colorbar before comparing the teams, because we chose to re-adjust the colorbar scale for each team for a better visualization.

The visualization of these figures can help understand in which locations each team was more active in taking shoots as compared to the usual level of shot activity in that zone. This can reflect in part the strategy taken by the team during that season. This strategy could also be correlated with the success of that team during that season.

We consulted the complete league standings on the NHL webside (https://www.nhl.com/standings/2016/league). We note that the Colorado Avalanche was ranked as the last team in the league for the 2016-2017 season, with as few as 48 points total. On the contrary, the Colorado Avalanche was ranked as first of the league for the 2020-2021, with 82 points total and winning the Stanley Cup. This does not directly reflect in the shot maps, since the shot map displays all shots, not only goals. For the 2016-2017 season, the shot map shows that the Colorado Avalanche were doing many shots in excess (up to 120% of the league average for some locations on the ice), specifically in the neutral zone face-off spots (especially left side), and also from the boards behind the goalie. This suggests that shooting from these areas was not successful in achieving goals. On the contrary, for the 2020-2021 year, the shot map of the Colorado Avalanche shows a shot rate per hour overall closer to the team average, except that an excess of shots were taken from the zone near the referee crease (left side on the plot). This suggests that shooting from that area might have been a good strategy to achieve goals. However, these hypotheses would need to be confirmed in further work that could draw for example shot maps only for the shots that were successful in achieving goals.

Here, we compare the Buffalo Sabres and the Tampa Bay Lightning, while considering that the latter ranked first (for total points) in 2018-2019 and won the Stanley Cup both for 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 seasons. As a comparison, the Buffalo Sabres has been struggling and ranked 27th, 25th and 31th (for total points) for those three years. We thus compare the shot maps of teams for these three years.

The patterns reflected by shot maps for these years shows a clear difference, when focusing on the locations from where the shots were taken. We note that while the Tampa Bay Lightning has taken an excess of shots of the attacking zone (2018-19, and 2019-2020 seasons), and also from the boards just behind the goalie (2019-2020 and 2020-2021 season). On the contrary, the Buffalo Sabres were taking a number of shots close to the league average, and the only areas in which they were taking excesses of shots were further from the goal, for example, they were taking shots from near the referee crease or from close to the ice center.

These comparisons suggest that some teams (here, the Tampa Bay Lightning) are more successful in winning when taking more shots from the attacking zone or from the boards behind the goalie, than other teams (here, the Buffalo Sabres) that took shots from further on the ice. Overall, it suggests that not only the excess of shots by itself, but the location of these shots, has an impact on the performance of the team.

However, this does not give the complete picture. First, all the comparisons done here were done visually, that is, we did not conduct statistical testing nor predictive modelling assessments. Second, we considered only the excess shot rate per hour stratified by all locations on the ice, not whether these shots actually resulted in goals. This does not give us information on the proportion of each shot that achieved goals in each location. For example, we see that the Buffalo Sabres were taking many shots from a furthest distance, and this is associated with the fact that this team did poorly in that season, but we did not directly assess the mechanism involved in the relationship between the shots in question and their unsuccessful results. Finally, it is possible that some locations of shooting do not directly result in goals, but have a broader impact on the game, by either making later goals possible for the team involved or making this team vulnerable to shots by the other team. Overall, these limitations highlight the necessity to be very careful when making causality or mechanistic assumptions from solely the visualization of data.

Conclusion

The present project is a good example of how sports data can be obtained from a publically available API, and made into a data format that can be used for advanced, interactive visualizations. Some limitations of the present work include that the conclusions drawn here from the data are based solely on data visualizations, and not yet on thorough predictive modelling. Further work could focus on using the formatted data for tasks such as feature selection and machine learning.

Authors

Vaibhav Jade: First year student of MSc. Computer Science at UdeM.

Mohsen Dehghani: Master’s degree in Optimization 2010-2013 and student of DESS in Machin learning at MILA 2022-2023. I start a master’s degree in Machin learning at MILA 2022-2023 love to show how to apply theoretical mathematical knowledge to real-life problems by using computer languages such as Java or Python.

Aman Dalmia: First year student of MSc. Computer Science at UdeM, have an interest in Information Retrieval and Natural Language Processing.

“Don’t create a problem statement for an available solution, rather work towards a solution for a given problem”

Raphaël Bourque: Graduated from Medicine, presently doing residency training in Psychiatry and at the Clinician Investigator Program, and studying at the MSc in Computationnal Medicine. My current research work is in Genetics (CHU Sainte-Justine), and I am very interested in the applications of data science and machine learning to evidence-based medical practice.

(Names are in ascending order)